The Sawdust Factory Presents:

Microscopes!

One Man's Idea of Excellent Indoor Entertainment

Part 1:

Compound Microscopes

Should one glance over my other web pages, suspicion may arise that I possess a certain passion for telescopes and astronomy. To this charge I plead guilty; Yes, I am fascinated by the gigantic vastness of the universe without our small sphere of existence, and the instruments we use to observe what we can of it. But in this page we go the other direction, for there is whole realm of tiny things which fall below the threshold of our unaided vision, and it exists right here, right now, and it is all around us. Given my natural awe of the cosmos, is it any wonder I am likewise fascinated by the "reverse universe", and the equipment we use to see what we can of it also?

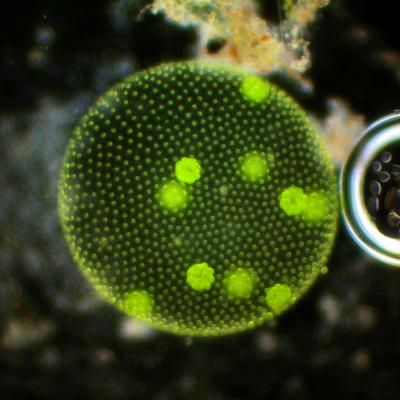

The green algae Volvox, 100X in dark field lighting, about 0.2 mm dia.

As usual, my toys had better be inexpensive because my many hobbies quickly outstrip funding capacity. Fortunately, I can make microscopy doable by specializing in vintage microscope equipment, specifically American Optical/Spencer stuff. While more modern microscopes can cost many hundreds while not always delivering solid quality, or many thousands for top flight "name brands", the following professional grade instruments from yesteryear are practically dirt cheap for the patient eBay shopper. All the scopes seen here can be had for less than $200 when you know what to look for.

Above: how it all started: a Christmas present when I was a kid in the mid 60's. I loved this thing!

(Tasco 75X - 300X - 600X, which was used at 75X 99.99% of the time. Very little, if anything, was possible with the higher powers.)

| Right: Portrait of an old friend: my first

"real" microscope.

The little Tasco did a fine job of hooking me on microscopy for life, so as a young adult I wasted little time acquiring this pre-war Spencer Model 33 MH monocular microscope as surplus from the University of Houston biology lab in the early 1980's. This instrument had been enduring the rigors of the classroom since it was new in 1940, and I can never get over how tight, solid, and relatively unscathed it remains today. Its age may be somewhat evident in the styling and present finish, but certainly not in function; it works like brand new - buttery smooth and crisply precise. Which is half the fun of owning and using older scopes like this: just feeling those frictionless gliding motions whenever you turn a knob. It's also surprisingly heavy. Microscopes of this make and era just have a particularly lovely feel to them all the way around! And ya just gotta dig the vintage look!

|

|

|

Quite a long spell later, this very closely related pre-war "Black Beauty" followed me home: a Spencer Model 13 MLH with inclined binocular head. Using both eyes was a huge stride forward in observing comfort, which led me to spend much more time observing; and that is when the hobby really took off. But because the cost of going binocular is a need for greater illumination intensity on account of the beam splitter and prism arrangement inside the head (see below), I quickly acquired a Spencer 735 research grade lamp from the same era to go with it ... and then set about learning how to use it properly. This advanced focusing lamp with iris diaphragm not only provides more robust illumination, but allows me to set up for true Kohler illumination*, which dramatically improves contrast and resolution over a simple illuminator as seen with the Model 33 above. A piece of thin plywood underneath is marked with lamp and stand positions to make setup easier, as achieving true Kohler can be a little tricky. The Spencer Lens Company actually offered a similar wooden board accessory for this very purpose, and spotting it while researching old catalogs is where the idea came from. Wonder if any original ones still exist? To this scope I added a set of modern Olympus objectives and modern wide-field eyepieces. It is now leaps and bounds ahead of my original one-eyed Spencer! |

|

* Köhler illumination is a lighting technique that generates extremely even illumination across the field of view, and is adjustable to the requirements of varying objective lens/eyepiece combinations. It is more or less ubiquitous in intermediate to advanced modern microscopy.

|

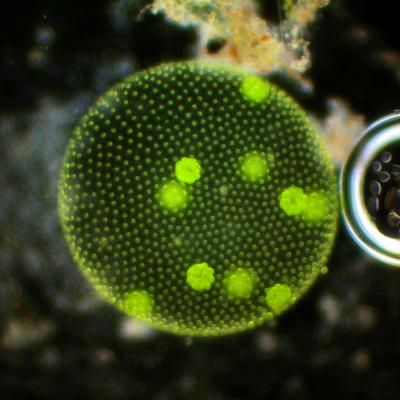

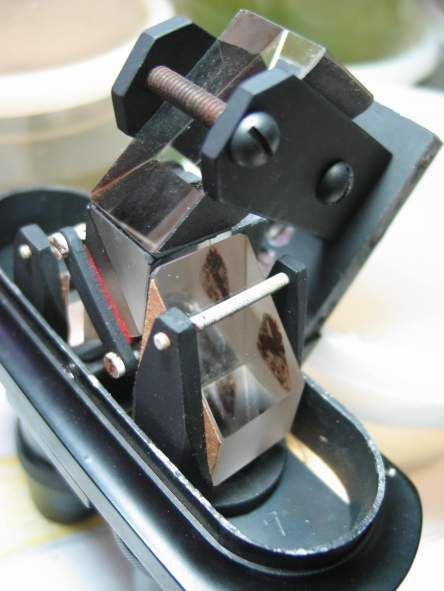

Here's the inside a Spencer Model 13 bino head: lots of prisms and a beam splitter. It is upside-down in this picture. There are something like ten optical surfaces that the light must pass through or bounce off en route from objective to eyepieces, plus one beam splitter. A monocular 'scope has none of this; light passes directly from objective to eyepiece with no middleman. A seemingly simple step up from one eyepiece to two is actually an order of magnitude in complexity, cost, and lighting requirement. Also because of all that extra glass, keeping things clean is very important, and that is why the head is taken apart in this picture -- for cleaning. |

|

|

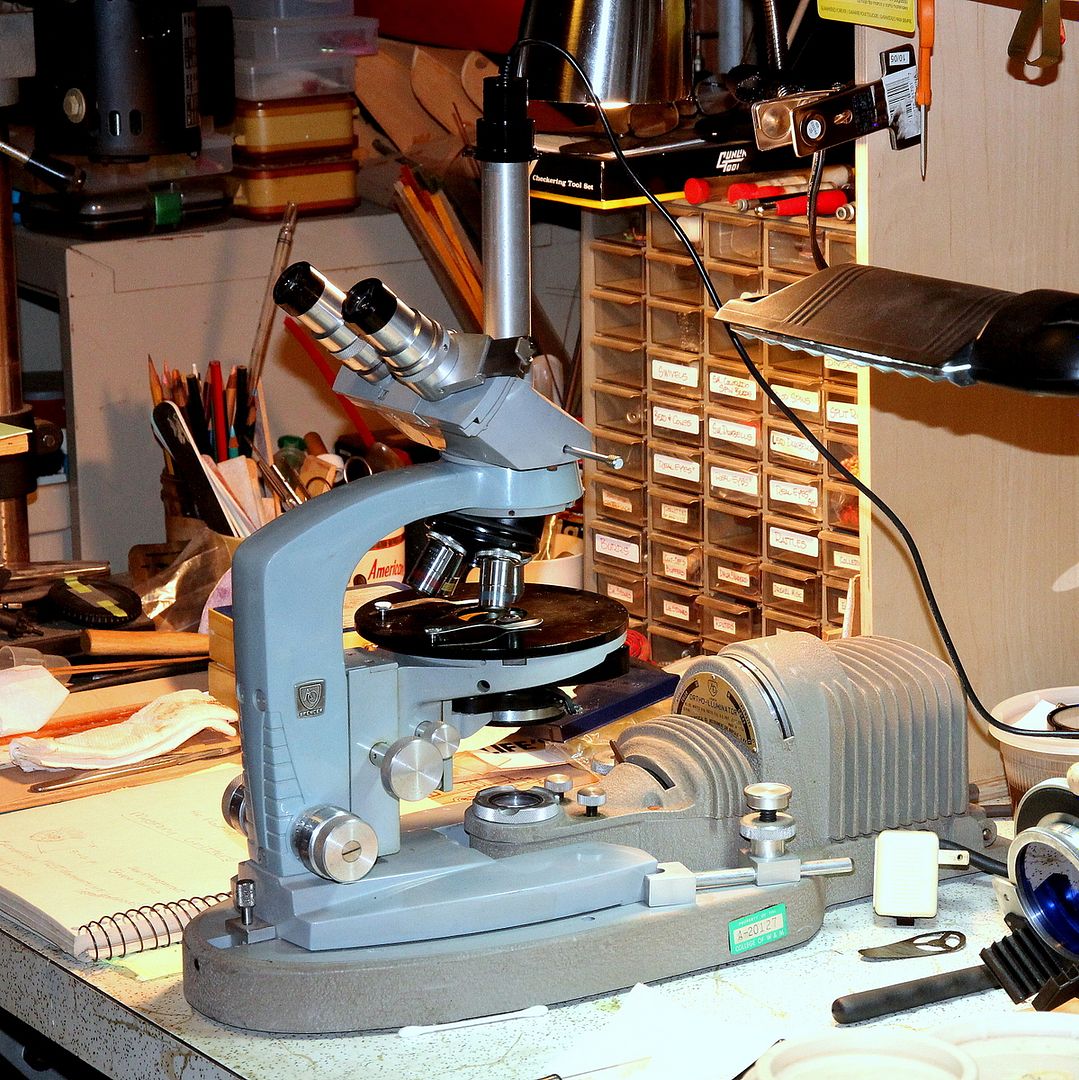

Next to come along is this beautiful

and very complete AO Spencer Series 2

PhaseStar of about the same vintage as its newest owner: me. Circa mid to

late 1950's.

Featuring phase contrast* in four objectives, it is seen here perched on an AO Spencer Ortho-Illuminator, which provides true Kohler

illumination; designed for film photomicrography as well as visual

use, it is more than adequate for digital imaging.

Speaking of which, the device atop the vertical trinocular tube is my first dedicated camera, a Celestron digital imager. While perhaps no miracle of performance, and for all practical purposes you must provide your own software, it is inexpensive and adds immense enjoyment to the hobby, so all things considered, I call it well worth the money. I have since upgraded to an Amscope 3 MP USB Camera, which comes with very nice software. This scope also features a very seldom seen or mentioned "Micro Glide" stage. You gently push it in any direction, and it indeed glides in a very precise and controlled manner. It's great for scanning about, and simply unbeatable for following live protists as they dash about in a pond water sample wet mount! Even though I have to say I prefer an X-Y mechanical stage, I am delighted to own and get to know this one. History Note: About the time the Series 2 and 4 stands appeared, the name American Optical, or AO, took precedence over Spencer. |

* Phase contrast is a method of altering the illumination to produce a harmless "virtual staining" effect that renders transparent microorganism specimens more visible, whereas conventional chemical staining methods would kill them. This allows living micro algae and "wee beasties" to be observed and studied (and often released back into their microquaria afterwards).

Here I made something of an epochal leap from the 160mm tube length optics of yore, to the more recent infinity corrected gear, when I assembled this AO Series 10 with 1031 lamp from parts and pieces collected over time from eBay. The very satisfactory result features a startlingly excellent set of rare bright phase contrast objectives in four magnifications. It is also equipped with polarizing capability. With this setup I can switch between bright field, dark field, phase contrast, and POL, with a few simple adjustments in seconds. The views are simply wonderful. A word about AO Series 10 illuminators: The halogen bulb 1031 lamp is often considered the most desirable of the several offered for Series 10 stands because it's center-able, and has a self-contained transformer that eliminates a separate power supply transformer, which is often missing in today's bargains, and bad for bench clutter when it is present. The halogen bulb 1036 and 1036A lamps are similar, but the 1036A lamp has a centering adjustment, the 1036 does not. The incandescent bulb 1037 is a simple diffuse substage light which gives no adjustment whatever other than on and off. This scope has become my travel companion with its relatively compact design and sleek, highly functional AO case. Originally equipped with the 1031 lamp, I have reconfigured a 1036A to LED which operates on a 4 AA battery pack tucked into the base. AO Series 10 scopes hail from the 1960's.

|

|

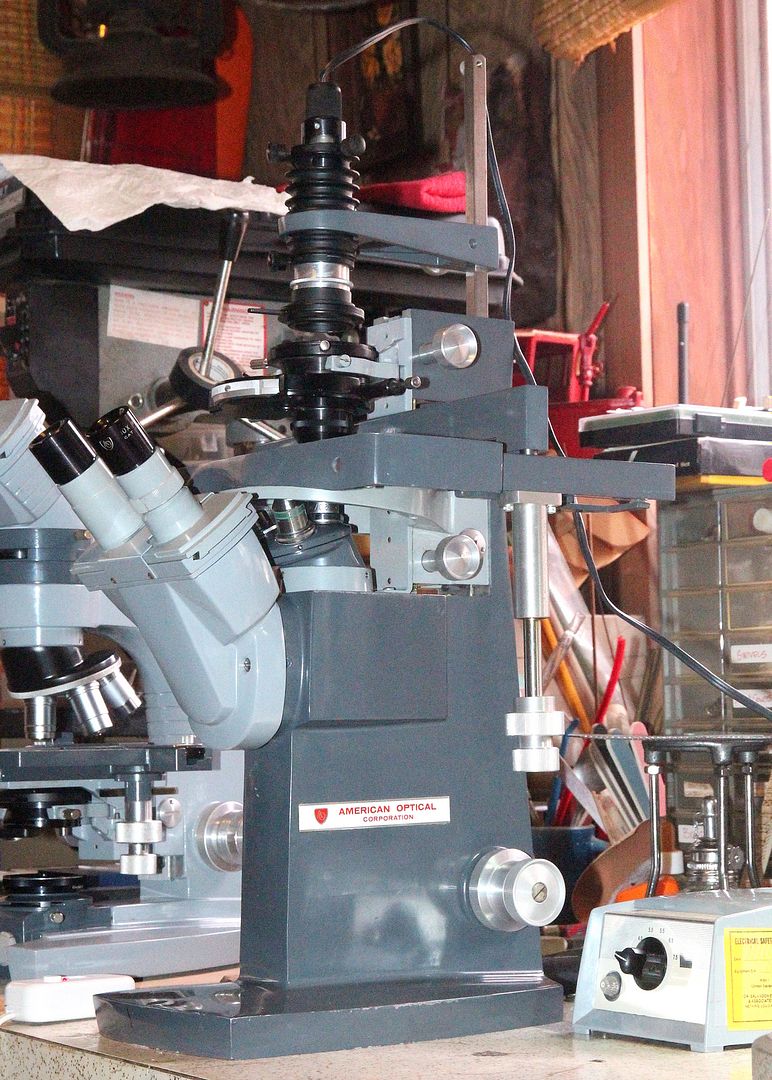

| Next is an American Optical

Model 1810 inverted microscope with dark phase contrast.

"Inverted microscope", what the heck is that? Why, it's just what it sounds like: an upside-down microscope! With this arrangement, the light source is up at the top, the condenser below it, then the stage. Underneath the stage is the nosepiece with objective turret. So instead of looking down upon the specimen, as with conventional microscopes, you peer up at it from below with this baby. Why? Simply put, the idea is to maintain a constant working distance between objective and sample, which allows observation of living protists and cultures in much larger sample containers which more closely approximate natural environments. Inverted microscopes are occasionally referred to as "biological microscopes" for this reason. This is not only hugely useful for the study of protozoa and microflora, but let's face it - inverted microscopes are just plain cool looking! This model also hails from the mid 1960's.

|

|

|

|

A real workhorse:

AO Series 120 with 100W lamp house converted to LED, phase contrast condenser, POL, and 5

objective nosepiece. The plan achro dark phase contrast objectives are absolutely marvelous performers.

This one came to me at a bargain price because it was missing its bulb holder and power supply, and replacements are notoriously difficult to obtain. But I wanted to experiment with an LED light source, so it was the perfect deal for me. The conversion works even better than hoped: more than sufficient intensity, color a very neutral white, and the lack of heat in the lamphouse is a real wonder. Guess I can forget about using the lamp cooling vent as a warmer for the coffee mug now. The Series 120 differs from the more commonly seen 110 by having a somewhat bulky lamphouse "annex" attached to the rear of the spine, which, in addition to the lamp, contains a set of three filter wheels (behind the fine focus knob in photo) that give a ton of options for adding filter combinations to the light path. The 120 originally required a separate transformer/ power supply, and together with the lamphouse takes considerably more bench space than the 110. The LED conversion is totally on-board, eliminating the separate power supply. This model is circa 1978, the year I would have graduated high school had I stuck around a little longer. History Note: About this time the name begins to morph into Reichert. |

| In a bit of a departure, my latest baby: a Zeiss WL stand featuring DIC and phase contrast. This one has been converted to 100W lamp (and coffee mug keeper-warmer!), and sports a rotating biological stage. |  |

My page on Photography Through the Microscope

My page on Micro-Aquariums and a Homemade Slide Ringing Table

Many thanks for to P. S. Neeley for his spectacularly helpful web pages! Click Here for his AO Spencer Microscopes site.

I have learned a great deal from internet discussion sites, and can recommend the following:

Microscope Restoration & Collection Yahoo Group

The Amateur Microscope Forum Yahoo Group

The Original Microscopy Yahoo Group

MicrobeHunter.com Microscopy Forum

Cloudy Nights Microscopy Forum

Part 2:

Stereo Microscopes

Most folks who own and use microscopes keep two types handy: compound microscopes, as seen above, and stereo, or "dissecting", microscopes as presented for your amusement below.

Very simply put, Compound microscopes are for high power viewing of very tiny subjects, and stereo microscopes for lower power viewing of relatively large items. Stereo microscopes are often used for examining such things as coins, insects, electronics, etc., in part because they give true stereoscopic views, which means you get natural depth perception in your magnified images, very cool!

| Meet another another old friend

from many years back: a Bausch & Lomb StereoZoom, enhanced with matching B&L Nicholas illuminator

lamp and transilluminator base, all vintage

early 1960's. An AO Model 651 lamp provides additional lighting for

scouting out those wee beasties in the sample cups.

Stereo microscopes differ from the compound microscopes by giving correct-image views (not reversed or upside-down), and offer hugely greater working distance between specimen and lenses so you can actually manipulate subjects while viewing. There are actually two complete separate optical trains for each eye, which gives true natural stereo vision with attendant depth perception just as the eyes normally have. Very cool to play with, and insanely handy for extracting the tiniest splinters from fingers with minimal fuss -- a great item for a woodworker to own! This one provides 10X to 25X magnification with a fluid, continuous zoom feature operated by the knob on top of the head. |

|

| A nice find: I ran across

this Bausch & Lomb stereo microscope in an antique shop, and for $30 couldn't pass

it up. Dating from 1936,

it yields a fixed magnification of 30x. It is quite robustly built, came with

a beautiful original wooden case,

and sports the sharpest optics ever.

You can see the the twin objectives looking down at the specimen stage on this model. Two complete microscopes working together to form one image. Great fun to use!

|

|

|

|

Left: AO Spencer Model 26L from

1951. Right: Spencer Buffalo Stereoscopic Microscope No. 25L (as listed in

the catalog) from 1944.

EBay rewards the patient watcher: I snagged both of these for little over half a C-note each. Both feature a rotating turret with 1X, 3X, and 6X objective pairs. I have all the eyepieces originally offered: 9X, 12X, 15X, and 18X. Now to fill out the collection with all the objective pairs I don't yet have: 7.5X, 2X, 4X, and 8X, which will yield a magnification range from 6.3X to 144X. The quality of manufacture is startling; they're surprisingly weighty, and the heavy steel focus knobs - no plastic in these babies - operate with unbelievably smooth precision. In both cases focus operates on a double dovetail system to cover a range from as low as the table top, to 4" above the stage plate. And you must get into some pretty fancy gear before you exceed the resolution of these optics. |

|

|

Here's a whole pile of vintage

AO/Spencer junk for you, if you call mid 1980's vintage: a model 58 "Cycloptic"

stereo scope, and two contemporary AO illuminators, one a model 655

Nicholas type inserted into the holder at the top of the microscope's

spine, and the other a model 651 directed obliquely at the specimen.

Again, photo depicts what it looks like when some strange nut case spends hours peering into the wee world of micro beasties in water samples taken from local ponds (nut is behind camera for photo). This is a different type of stereoscopic microscope from those above: it a Common Main Objective type, or CMO for short, and often referred to as a Cycloptic since both halves "look through" a single objective lens. The other type, with two objective lenses, are called "Greenough" type, after the inventor. If you want to know more, click here for an excellent article. Also different: instead of a zoom feature, this scope has five different magnification levels which you dial in with the large side knob, from 7X, 10X, 15X, 20X and 25X. There's a magnificent list of pros and cons for each type; a contest between the convenience a zoom function, or the "cleaner" optics of the selectable magnifications results no clear winner except for the guy who has one of each. |

| An example of just how inexpensive this stuff can get:

this is an AO "Forty"

student grade stereo microscope, which is particularly aptly named because it came to me for forty bucks. While it's no miracle of microscopic wonderfulness since it lacks the general polish, removable eyepieces, smoothness of operation, and multiple magnifications of the more advanced models, and exhibits noticeable spherical aberration at the edges, the plus side is strong: it features built-in top and bottom lighting, it's practically bombproof, and it came with a great carry case. Oh yes, and it was dirt cheap! I'm thinking maybe travel scope perfection? |

|

|

|

And now for something completely

different.

Not really, just another way of enjoying stereo scopes, this time a Swift Stereo Ninety. I bought this one, again, at a bargain price, because its design allows easy adaptation to use on a photo tripod via homemade cradle. With low magnification and long working distance typical of stereo scopes, it's perfect for studying tiny aquatic organisms in a very natural habitat as seen here. Micro aquariums are easy to build at home from window glass and silicone sealant purchased at the local hardware store. A macro photography focus rail is also very helpful for this application. |

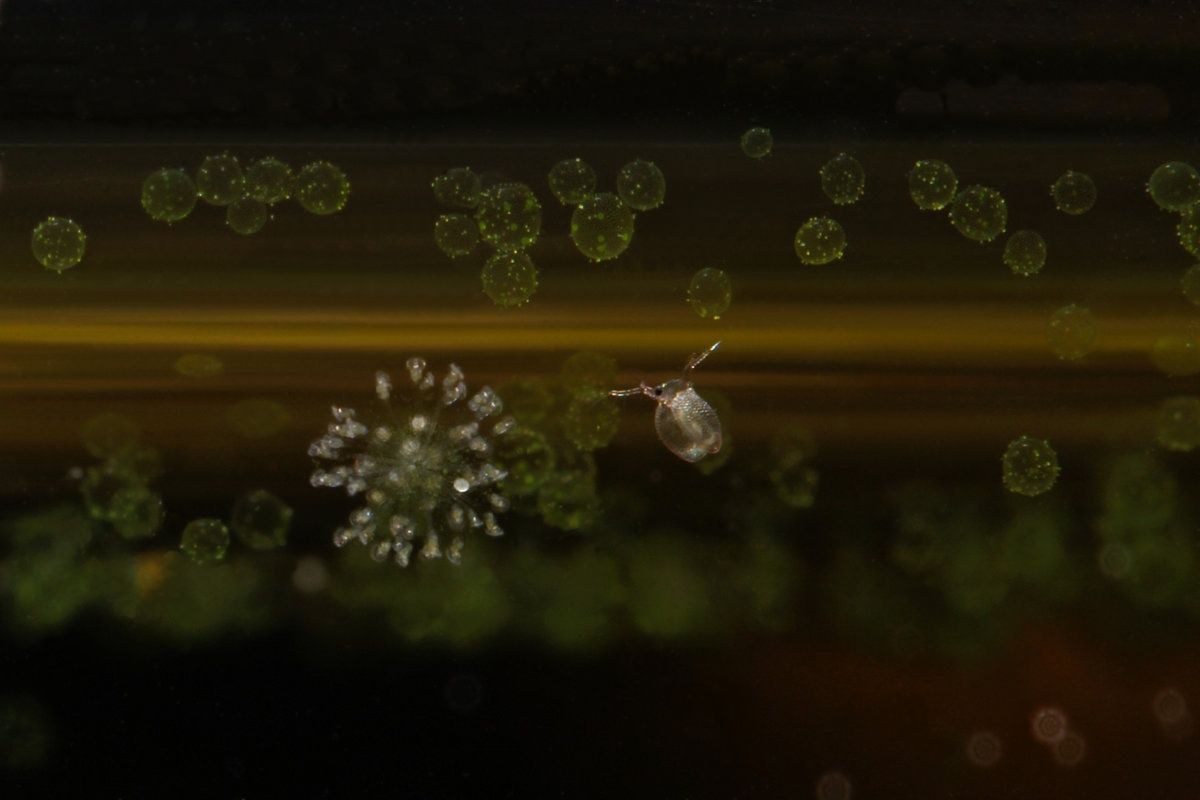

| This scene is just as one might

expect to see in a rig such as that above.

Conochilus, Daphnia, and Volvox are the cast of characters in this wee drama. And that is why we do it. See my Flickr Album for more. |

|

My page on Photography Through the Microscope

My page on Micro-Aquariums and a Homemade Slide Ringing Table

Return to the Sawdust Factory Table of Contents

Email Kurt Maurer at: NGC704@aol.com